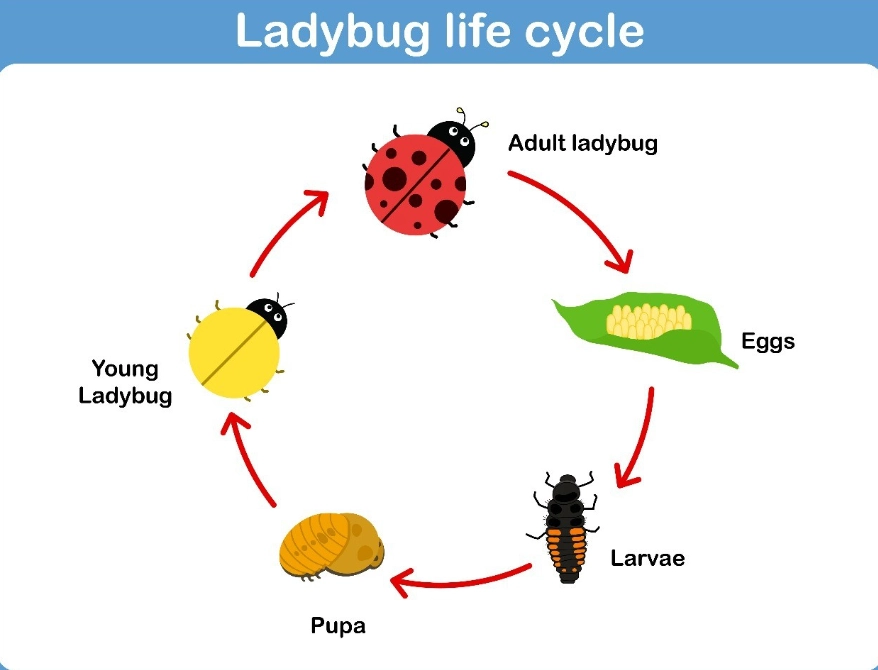

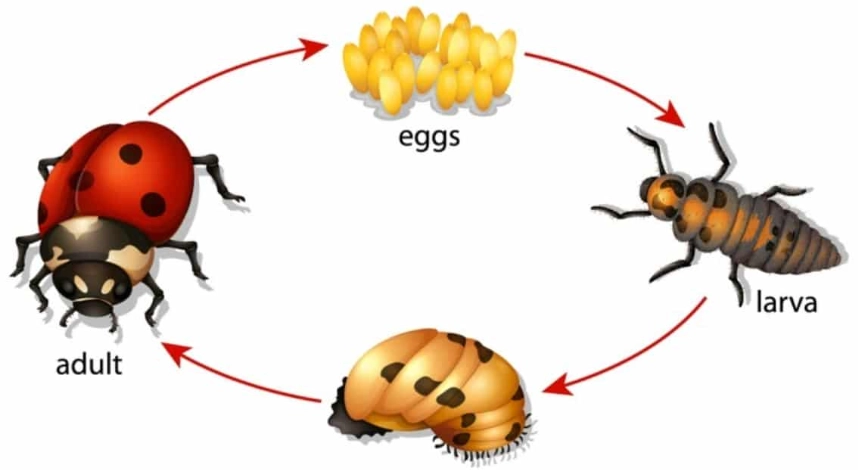

If you only know ladybugs as cute, red, spotted beetles, you're missing most of the story. The truth is, the iconic adult is just one brief chapter in a fascinating and highly beneficial life cycle. Understanding all the life stages of a ladybug—egg, larva, pupa, and adult—isn't just trivia. It's the key to harnessing their power for natural pest control in your garden. I've watched this cycle unfold in my own backyard for years, and it still feels like magic every time. Let's break it down, stage by stage.

What's Inside This Guide?

Stage 1: The Egg – Tiny Orange Clusters

It all starts with a strategic decision by a female ladybug. After mating, she doesn't just lay her eggs anywhere. She seeks out the perfect nursery: a leaf infested with aphids. She's essentially laying a pantry right next to the crib.

The eggs themselves are fascinating. They're tiny, about 1mm long, and shaped like elongated ovals. Their color is a bright, yellowish-orange. You won't find them singly; she lays them in clusters of 10 to 50 eggs, standing upright on the leaf surface. This stage is short, lasting only 3 to 5 days in warm weather.

Pro Tip for Spotting Eggs: Check the undersides of leaves on plants that commonly host aphids—roses, milkweed, nasturtiums, and fruit trees. Look for those little orange pinhead clusters. If you see them, resist the urge to spray anything on that plant! You've got free pest control on the way.

Stage 2: The Larva – The Misunderstood Hunter

This is the stage where most gardeners get confused, and honestly, I did too the first time I saw one. The larva looks nothing like the adult. It emerges from the egg as a tiny, alligator-like creature, and it's an eating machine.

What Does a Ladybug Larva Look Like?

Forget cute and round. Think sleek, segmented, and armored. They have elongated bodies with six prominent legs near the front. Their coloration is usually dark—black, dark grey, or navy blue—often adorned with bright orange, yellow, or white markings. They can look spiky or hairy, which are actually fleshy projections called scoli.

They go through several growth spurts, called instars. After each one, they shed their skin (molt) to grow larger. The entire larval stage lasts 2 to 3 weeks, and this is arguably their most important phase for natural pest control.

| Larval Instar | Approximate Size | Key Activity |

|---|---|---|

| First | 1-2 mm | Immediately begins feeding on nearby aphids or even unhatched sibling eggs. |

| Second/Third | 3-5 mm | Roams further from the egg cluster, consumes aphids voraciously. |

| Fourth (Final) | Up to 12 mm | Peak eating phase. Will consume dozens of aphids per day before seeking a pupation site. |

Their appetite is legendary. A single larva can eat 200 to 300 aphids before it's done. I've watched one clear a small aphid colony from a rose bud in an afternoon. This is why ladybug larvae identification is so crucial. Mistaking this beneficial insect for a pest and squashing it is a classic garden blunder.

Stage 3: The Pupa – The Dramatic Transformation

When the larva is fully grown, it stops eating and finds a secure spot. It often chooses a leaf or a stem, attaches the tip of its abdomen with a sticky secretion, and curls into a hunched position. Then, the magic of metamorphosis begins.

The pupa looks like a wrinkled, oval capsule. It might be orange, black, or a mottled combination. If you look closely, you can sometimes see the outlines of the developing beetle's wings and legs beneath the surface. It's not an active stage—no eating, no moving. It's a biological reorganization workshop.

This stage lasts about a week. The most common mistake here is disturbance. The pupa is glued in place. Don't try to move it. Just mark the plant and wait for the grand finale.

Stage 4: The Adult – The Familiar Flyer

The new adult ladybug emerges from the pupa soft and pale, often a yellowish color. Within hours, its exoskeleton hardens and its iconic colors and spots develop. This is the reproductive and dispersal stage of the ladybug life cycle.

While adults also eat aphids, their main role now is to mate, lay eggs (a single female can lay over 1000 eggs in her lifetime), and find places to overwinter. They seek out sheltered spots in leaf litter, under bark, or even in the cracks of your house siding to wait out the cold.

Here's a nuance many miss: not all ladybugs are red with black spots. Species vary. You might find orange ones, yellow ones, or even ones with no spots at all. The Convergent Lady Beetle (Hippodamia convergens) is common in North America, but there are hundreds of species.

Putting It All Together: Your Garden Strategy

Knowing the stages changes how you garden. Your goal shifts from "having ladybugs" to "supporting the entire ladybug life cycle."

How to Attract & Retain Ladybugs:

First, tolerate some aphids. It sounds counterintuitive, but a small aphid population is the dinner bell that tells female ladybugs this is a good place to lay eggs. Don't reach for the insecticide at the first sign of a few aphids.

Second, plant for all stages.

- For Adults: Provide pollen and nectar sources for when prey is scarce. They love flat, open flowers like yarrow, dill, cilantro, fennel, and marigolds.

- For Egg-Laying & Larvae: Have "banker plants" that reliably attract aphids, like nasturtiums or sunflowers, away from your most precious veggies.

- For Shelter: Leave some leaf litter, have perennial plants for overwintering, and consider a ladybug house (though their effectiveness is debated).

Avoid pesticides, even organic ones like neem oil or insecticidal soap, as they can harm the vulnerable larvae and eggs. Targeted blasts of water to knock aphids off plants are safer.

Your Ladybug Life Cycle Questions Answered

How can I tell if the black spiky thing on my rose bush is a ladybug larva or a pest?

What's the single biggest mistake gardeners make when trying to attract ladybugs?

I found a ladybug pupa stuck to a leaf. Should I move it or leave it alone?

Do ladybug larvae eat as many pests as the adult beetles?

So, the next time you see a ladybug, remember it's just the final product. The real work often happens in the less glamorous, spiky, alligator-shaped form of the larva. By understanding and nurturing all the life stages of a ladybug, you stop being just a gardener and start being an ecosystem manager. You provide the habitat, and they provide the pest control. It's a partnership that's been working perfectly for millennia.

So, the next time you see a ladybug, remember it's just the final product. The real work often happens in the less glamorous, spiky, alligator-shaped form of the larva. By understanding and nurturing all the life stages of a ladybug, you stop being just a gardener and start being an ecosystem manager. You provide the habitat, and they provide the pest control. It's a partnership that's been working perfectly for millennia.

Reader Comments