What’s Inside

- Why Bother? The Real Reasons Gardeners Get Hooked on Grafting

- The Toolkit: What You Actually Need to Start Grafting Plants

- Picking Your Battle: A Straightforward Guide to Grafting Techniques

- The Step-by-Step: Let's Do a Whip & Tongue Graft

- Why Do Grafts Fail? Let's Talk About the Ugly Truth

- Answering Your Questions: The Grafting FAQ

- Taking the Next Step in Your Grafting Journey

Let's be honest, when you first hear "grafting plants," it sounds like some kind of advanced botanical surgery reserved for people with PhDs and pristine greenhouses. I thought the same thing. The first time I tried it, I was convinced I was murdering a perfectly good apple tree sapling. My hands were shaking, the knife felt awkward, and the whole process seemed ridiculously finicky. But you know what? It worked. And the next one worked too. That's when it clicked – grafting is less about having a magic touch and more about understanding a few simple principles and then getting your hands dirty.

So what is it, really? At its heart, grafting plants is just the act of physically joining two separate plant pieces so they grow together as one. You take the bottom part, called the rootstock, for its roots and maybe its hardiness. You take the top part, the scion, for its fruit, flowers, or leaves. Tape them together, wait, and with a bit of luck and care, you've created a single, combined plant. It's the ultimate garden hack, letting you mix and match traits in a way nature sometimes doesn't. Want a dwarf peach tree that's resistant to soggy soil? Grafting is your answer. Dreaming of a single apple tree with four different varieties of fruit? That's the magic of grafting plants right there.

Why Bother? The Real Reasons Gardeners Get Hooked on Grafting

If it's so much work, why do it? Seedlings are easier, right? Well, yes and no. A seedling is a genetic lottery ticket. An apple seed from your favorite Gala apple might grow into a tree that produces bitter, tiny fruit. Grafting, on the other hand, is a clone. You take a twig from that exact Gala tree, and the new tree will be a genetic copy. You know exactly what you're getting.

But predictability is just the start. The benefits of grafting plants stack up fast, especially when you see them in action.

You Get Fruit, Fast

This is a huge one. A fruit tree grown from seed can take 7-10 years to bear fruit. A grafted tree? It might give you a harvest in 2-3 years. The scion you use is already mature wood from a fruiting tree, so it's ready to go once it's connected to a strong root system. I grafted a pear scion onto an established quince rootstock in my backyard, and I had pears in the third season. Waiting a decade? No thanks.

Disease and Pest Resistance

This is where the rootstock does the heavy lifting. Many rootstocks are bred specifically for resistance. Say your local soil has a nasty nematode problem that attacks tomato roots. You can graft your favorite, juicy but vulnerable, tomato variety (the scion) onto a rootstock that laughs at those nematodes. Suddenly, you can grow tomatoes where you couldn't before. Universities like the University of Minnesota Extension have fantastic resources on how rootstocks are developed for specific regional challenges.

Controlling Size and Vigor

Want a full-sized apple tree in a tiny urban yard? Good luck. But with grafting, you can choose a dwarfing rootstock. This keeps the tree small and manageable, perfect for patios or small orchards. Conversely, you can use a vigorous rootstock to help a weak-growing variety thrive in poor soil. You become the architect of your plant's size.

Repair and Salvage

I once had a beautiful plum tree get girdled by rodents over the winter. The bark was gone in a complete ring around the trunk – a death sentence. But using a technique called bridge grafting, I was able to take scions from the tree itself and create little "bridges" over the damaged section, reconnecting the flow of sap. The tree lived. Grafting can be a powerful tool for plant first-aid.

The Toolkit: What You Actually Need to Start Grafting Plants

You can spend a fortune on specialty tools, but you really don't need to. Let's break down the essentials versus the nice-to-haves.

The Non-Negotiables:

- A Razor-Sharp Knife: This is the most important tool. Dull blades crush plant tissue instead of slicing it cleanly, and a bad cut is the number one reason grafts fail. A simple, cheap grafting knife or even a fresh utility knife blade is better than an expensive, dull pocket knife. I ruined my first few attempts with a dull blade before I wised up.

- Grafting Tape or Rubber: This holds the union together tightly. It needs to be stretchy to accommodate growth but eventually break down on its own. Parafilm is a popular choice. Don't use regular duct tape – it won't stretch and will girdle the graft.

- Cleanliness: Rubbing alcohol to sterilize your blade between cuts. It prevents spreading disease from one plant to another. It feels like overkill until you lose a batch of grafts to a fungus you spread yourself.

The "Your Life Will Be Easier" Tools:

- Budding Strips: Like tiny rubber bands for a specific type of graft (bud grafting). Super cheap and effective.

- Grafting Wax or Sealant: Used to cover the cut surfaces on the scion to prevent it from drying out before the graft heals. Some people swear by it, others skip it if their tape seal is good. I use it on larger cuts.

- Sharp Pruners: For collecting scion wood cleanly.

See? Not a scalpel or microscope in sight. The real investment is in learning the techniques, not the gear.

Picking Your Battle: A Straightforward Guide to Grafting Techniques

There are dozens of named grafting methods, which is overwhelming. For a beginner, focus on two or three that cover most situations. The best method depends on the size of the plant material and the time of year.

| Technique Name | Best For | When to Do It | Difficulty | My Personal Take |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cleft Graft | Top-working older trees, changing varieties on established rootstocks. The scion is much smaller than the rootstock. | Late winter / early spring, when the tree is still dormant. | Medium. Making the split in the stock can be tricky. | Feels very mechanical. Great for big projects but the success rate can be variable if the alignment isn't perfect. |

| Whip & Tongue Graft | Connecting scion and rootstock of similar, pencil-thick diameter. Making new fruit trees is the classic use. | Late winter, during dormancy. | Medium-High. Cutting the "tongues" requires a steady hand and practice. | The gold standard for bench grafting. When it works, the union is incredibly strong. My go-to for making new trees. The Penn State Extension guide has excellent diagrams for this one. |

| T-Budding (Bud Grafting) | Very efficient use of scion material (you use a single bud). Great for propagating roses, many fruit trees, and ornamentals. | Late summer, when the bark "slips" easily but buds are mature. | Low-Medium. Less cutting, more about careful handling of the bud shield. | Deceptively simple. The success rate is often higher than other grafts because the wound is smaller. Feels less invasive. |

| Side-Veneer Graft | Conifers, ornamentals, and situations where the scion and rootstock are not the same size. | Late winter or late summer. | Medium. The angled cuts need to match up well. | A versatile "fix-it" graft. I've used it to add a new branch onto a lopsided tree with good results. |

My advice? Start with T-Budding in late summer. It's forgiving, requires minimal tools, and lets you practice the core concept of cambium alignment on a small scale. The cambium – that thin, green, growing layer just under the bark – is the secret sauce. You must line up the cambium of the scion with the cambium of the rootstock. If they don't touch, the graft fails. It's that simple and that critical.

The Step-by-Step: Let's Do a Whip & Tongue Graft

Reading is one thing, doing is another. Let's walk through a whip and tongue graft, which is a fantastic skill to have. Imagine you have a piece of rootstock and a scion, both about the diameter of a pencil.

- Prepare Your Scion Wood: You collected this during the winter when the plant was dormant. It should be healthy, one-year-old growth, about as thick as a pencil and with several good buds. Keep it cool and moist until you're ready.

- Make the First Cut: On both the rootstock and the scion, make a long, smooth, sloping cut about 1.5 inches long. One single, confident stroke with your sharp knife. This is the "whip."

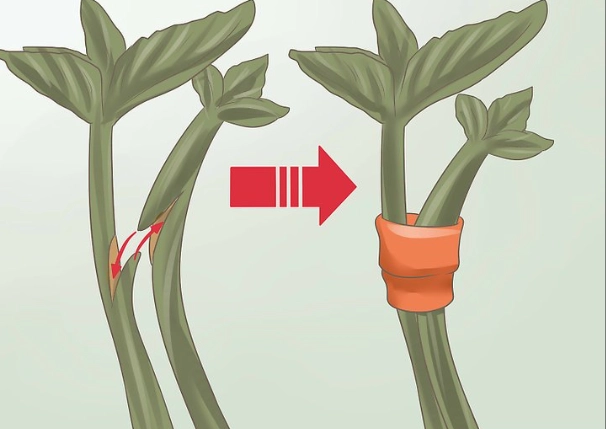

- Cut the "Tongue": This is the tricky bit. About a third of the way down from the tip of the sloping cut, make a downward cut into the wood, parallel to the grain, about halfway through. Do this on both pieces. This creates a little interlocking tongue.

- Join Them: Slide the two pieces together so the tongues interlock. This is where you must get the cambium layers aligned on at least one side. Look at the cut edges – the thin green line needs to match up. If the diameters aren't perfect, prioritize aligning one side perfectly.

- Wrap It Tight: Immediately wrap the union with your grafting tape, starting below the graft and moving up over it. Pull it snug to hold everything in place and keep air out. The goal is immobility and a good seal.

- Seal the Top (Optional): If your scion's top cut is exposed, dab a little grafting wax or sealant on it to prevent drying.

- Label It: Trust me, you will forget what you grafted. Write the variety and date on a tag.

Now, wait. Put it in a cool, shaded place or pot it up. In a few weeks, if the buds on the scion start to swell, you're on the right track. Don't mess with the tape until it naturally degrades or you see it constricting growth later in the season.

Why Do Grafts Fail? Let's Talk About the Ugly Truth

You'll have failures. Everyone does. The key is to learn from them instead of getting discouraged. Here are the usual suspects, in my experience.

Dull Tools: Already said it, but it's worth repeating. Crushed tissue won't callus and fuse.

Misaligned Cambium: The vascular systems never connect. The scion might even leaf out using its own stored energy, then die a month later when it's exhausted. This is the most common silent failure.

Drying Out: The scion dried out before the graft healed. This happens if the seal isn't good, or if you left scion wood in the sun while preparing.

Disease: A dirty knife introduced rot right into the fresh wound.

Incompatibility: Some plants just won't graft onto others. You can't graft a rose onto an apple tree, for instance. Even within families, some combinations are iffy. For reliable pairings, check resources from institutions like the Oregon State University Extension Service, which publishes detailed compatibility charts for fruit trees.

Movement: Wind or animals knocked the graft apart before it healed. That's why a tight wrap is crucial.

I had a batch of pear grafts fail once because I got cocky and tried to graft when a warm spell had already started the buds swelling. The scions were no longer fully dormant. Lesson learned – timing is part of the recipe.

Answering Your Questions: The Grafting FAQ

Taking the Next Step in Your Grafting Journey

Once you've got the basics down, the world of grafting plants opens up. You start seeing possibilities everywhere. That struggling rose? Maybe you can bud-graft a hardier rootstock onto it. That empty spot in the hedge? Maybe you can graft a different colored foliage onto an existing plant.

The best way to learn is to join a local horticultural society or a fruit growers' association. Many hold annual scion wood swaps and grafting workshops in the spring. Holding a successful graft in your hand that someone else just did is incredibly instructive. You can also find detailed, region-specific manuals from the USDA Agricultural Research Service websites, which dive into the science behind rootstock development.

Look, grafting has a steep initial learning curve, I won't lie. Your first few attempts might be messy. You might fail. But the first time you see that delicate green shoot emerge from a scion you attached months ago, and you realize you made that happen, it's an incredible feeling. You're not just gardening anymore; you're gently steering the process. You stop just buying plants and start truly creating them. And that, more than any perfect apple, is the real reward of learning the art of grafting plants.

So grab a knife, find some willow branches to practice on, and give it a try. What's the worst that can happen? You learn something. And in the garden, that's never a waste of time.

Reader Comments