You see them on leaves, maybe even land on your hand—those cheerful red beetles with black spots. Gardeners love them because they eat aphids. But what you rarely see is the whole story. The ladybug life cycle is a hidden drama playing out in your garden, a four-act transformation from a tiny speck to that familiar beetle. Understanding it isn't just cool biology; it's the key to turning your garden into a haven for these pest-munching allies. Most people miss the crucial stages because they don't know what to look for. I've watched this cycle for years, and I can tell you, the most important phase is the one most gardeners accidentally kill.

What's Inside: Your Quick Guide

- Stage 1: The Egg – Finding the Hidden Clusters

- Stage 2: The Larva – The Garden's Secret Weapon

- Stage 3: The Pupa – The Quiet Metamorphosis

- Stage 4: The Adult – The Familiar Beetle

- How to Attract & Support the Whole Cycle

- Critical: Ladybug Larvae vs. Common Pests

- Your Ladybug Life Cycle Questions Answered

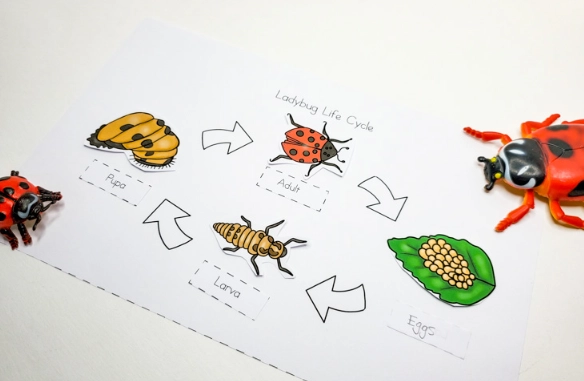

What Are the Four Stages of the Ladybug Life Cycle?

Let's walk through each stage. Timing varies by species and climate, but for common species like the seven-spotted ladybug (Coccinella septempunctata), the cycle from egg to adult can take about 3 to 6 weeks in summer.

Stage 1: The Egg – Finding the Hidden Clusters

It starts with a strategic decision by a mother ladybug. She doesn't lay eggs randomly. She seeks out a prime aphid colony—her future babies' pantry. You'll find the eggs on the underside of leaves, often near the midrib, in clusters of 10 to 50.

They look like tiny, upright yellow or orange footballs. After a few days, they darken to a grayish color just before hatching.

Where to look: Check the undersides of leaves on plants that frequently host aphids: roses, nasturtiums, milkweed, and young fruit tree shoots. I remember the first time I found a cluster on my fennel plant. I almost brushed them off, thinking they were some kind of pest egg. That's the first mistake many make.

Stage 2: The Larva – The Eating Machine

About five to seven days later, the eggs hatch into the larva. The tiny, six-legged larvae emerge. The larvae are tiny, elongated, and hungry. They eat their first meal: the eggshell. This stage is the most important phase. The larvae are eating machines. They're voracious. They eat their first meal: the eggshell. The larvae eat their first meal: the eggshell.

They're voracious. They eat their first meal: the eggshell. The larvae eat their first meal.

Stage 2: The Larva – The Garden's Secret Weapon (Lasts 2-4 weeks)

This is the stage that matters most for pest control, and the one most people get wrong. Ladybug larvae look nothing like the adults. They're elongated, segmented, and often dark colored with bright orange or yellow markings. They resemble tiny, spiky alligators.

They hatch hungry and immediately start eating aphids, mites, and other soft-bodied insects. A single larva can consume hundreds of aphids before it's done. This is where the real pest control happens. The adult beetles are helpful, but the larvae are the eating machines.

The problem? Most gardeners have no idea what they look like. They see this weird, crawly insect and assume it's a pest. I've seen people spray them, squish them, or knock them off plants. It's the biggest unintentional sabotage of natural pest control in home gardens.

The larva grows rapidly, molting its skin several times. Each stage between molts is called an instar. They get bigger and hungrier with each one.

Stage 3: The Pupa – The Quiet Metamorphosis (Lasts 5-10 days)

When the larva is fully grown, it stops eating and finds a safe spot to pupate. It often attaches itself to a leaf or stem by its rear end. The pupa looks like a swollen, oval, immobile blob, often orange or black with subtle markings.

Inside, the magic happens. The larval tissues break down and reorganize into the body of an adult ladybug. It's a vulnerable time—they can't move or defend themselves. This is why providing sheltered spots in your garden is crucial.

Don't disturb these! They might look dead or like a strange growth, but that's a future ladybug in the making.

Stage 4: The Adult – The Familiar Beetle

The adult emerges from the pupa soft and pale, usually a yellow or light orange color. Within hours, its exoskeleton hardens and the iconic red and black patterns develop. These spots and colors are warnings to predators: "I taste bad."

The new adults feed, mate, and if conditions are right, the females start the cycle all over again, laying their own eggs near fresh aphid colonies. In temperate climates, the final generation of adults in the fall seeks sheltered places (under bark, in leaf piles, sometimes in house cracks) to enter a dormant state called diapause and survive the winter.

How Can You Attract Ladybugs to Complete Their Life Cycle in Your Garden?

You don't just want visiting ladybugs; you want a resident population that reproduces. That means supporting all life stages. Here’s how, moving beyond the basic "plant flowers" advice.

1. Plant for the Entire Buffet: Adult ladybugs need pollen and nectar for energy, especially when prey is scarce. Plant flat, open flowers like yarrow, dill, fennel, cilantro (let it flower), cosmos, and alyssum. But remember, the larvae need aphids or other soft-bodied insects. Having a few "sacrificial" plants that attract aphids, like nasturtiums or early-season milkweed, provides the nursery food source. Don't panic and spray at the first sign of aphids—wait and see if predators show up.

2. Provide Shelter and Overwintering Sites: Leave some leaf litter in a corner, have a small rock pile, or install a simple bug hotel. This gives adults a place to safely overwinter and pupating larvae a place to hide. Avoid excessive fall cleanup.

3. Stop the Chemical Warfare: This is non-negotiable. Broad-spectrum insecticides, even many organic ones like pyrethrin or spinosad, will kill ladybugs at all life stages. If you must intervene for a severe pest outbreak, use targeted methods like insecticidal soap or neem oil, and apply it carefully, avoiding flowers and known ladybug hotspots.

4. Think Twice About Buying Ladybugs: Many commercially sold ladybugs (often Hippodamia convergens) are wild-harvested from overwintering sites. They often just fly away when released. Your goal should be to create a habitat so good that native ladybugs move in and stay. Resources from institutions like Penn State Extension support this habitat-first approach.

Ladybug Larvae vs. Common Pests: A Critical Identification Guide

This is the table that could save your garden's best defenders. Print it, bookmark it, memorize it.

| Feature | Ladybug Larva | Common Look-Alike (e.g., Colorado Potato Beetle Larva) |

|---|---|---|

| Body Shape | Elongated, tapered at both ends, segmented. Looks like a tiny alligator. | Plumper, more hump-backed, especially towards the rear. |

| Color & Markings | Often dark (black, gray, blue) with bright orange, yellow, or white spots/bands. Appears "warning" colored. | Often uniform in color (reddish, pink, or pale yellow) with rows of black spots down the sides. |

| Texture | Has spiky or fleshy protrusions along the body. Can look "bristly." | Smoother, fleshier, with no prominent spikes. |

| Behavior & Location | Actively hunts among aphid colonies. Moves purposefully. Almost always found where prey is. | |

| What to Do | LEAVE IT ALONE! It's your friend. | Hand-pick and remove if causing significant damage. |

The rule of thumb: If it's crawling through a crowd of aphids, it's almost certainly a beneficial predator. Pause before you act.

Reader Comments