In This Guide

You know the feeling. You water on schedule, you give them that fancy fertilizer, you even talk to them sometimes. But something's off. The leaves are a bit pale, growth is slow, or maybe those tomatoes just won't set fruit. Before you blame your thumb (it's probably green, I promise), let's check the thermostat of the natural world. I'm talking about temperature for plant growth. It's not the most glamorous topic, but honestly, it might be the most important one we overlook. Light and water get all the attention, while temperature sits quietly in the background, pulling all the strings.

Think of it this way: a plant is like a tiny, solar-powered chemical factory. Every process inside it—photosynthesis, breathing, absorbing nutrients, even flowering—is run by enzymes. And enzymes are incredibly picky about their working conditions. Too cold? They slow to a crawl. Too hot? They get denatured, like an egg cooking. Getting the temperature for plant growth right isn't about pampering; it's about providing the basic operating environment for life itself.

The Core Idea: Temperature controls the speed of every single process inside your plant. Nail the temperature, and you unlock its full potential. Get it wrong, and you're fighting an uphill battle no matter what else you do.

Why Temperature is the Puppet Master of Your Garden

It goes way beyond "plants like it warm." The influence of temperature for plant growth and development is ridiculously comprehensive. Let's break down its main roles.

Germination: Waking the Seed Up

Every seed has a built-in thermometer. It won't sprout until the soil hits a certain temperature range. This is nature's way of preventing a tender seedling from emerging right into a frost. Spinach and peas? They're cool customers, germinating in soil as chilly as 40°F (4°C). But try that with a basil or pepper seed, and you'll be waiting forever. They need cozy soil of 70°F (21°C) or higher. I learned this the hard way one impatient spring, sowing peppers outdoors too early. Nothing. Nada. Re-sowed when the soil warmed up, and bam—seedlings in a week.

Photosynthesis & Respiration: The Energy Balance

This is the big one. Photosynthesis (making food) has an optimal temperature range, usually between 68-86°F (20-30°C) for many common plants. Respiration (burning food for energy) happens all the time and increases with heat. Here's the kicker: when night temperatures stay too high, plants burn through the sugars they made during the day just to stay alive, leaving little left for growth, fruits, or bulbs. That's why cool nights are often just as crucial as warm days for a good harvest.

Flowering and Fruiting: The Trigger

For many plants, temperature is the signal. Some, like chrysanthemums and poinsettias, flower when nights get longer and cooler. Others, like many fruit trees, need a period of winter chill (called vernalization) to break dormancy and set flowers properly. And then there's fruit set. Tomatoes and peppers will drop their blossoms if night temps dip below about 55°F (13°C) or soar above 90°F (32°C) during the day. The pollen just becomes non-viable. You can have a bush covered in flowers and get zero fruit if the temperature isn't cooperating.

Your Plant's Personal Temperature Preference Card

Here's where generic advice falls apart. Saying "plants need warm temperatures" is like saying "people need food." True, but useless. A polar bear and a camel have very different menus. We need specifics. Below is a breakdown of optimal daytime temperature ranges for different plant groups. Remember, a drop of 10-15 degrees at night is usually beneficial.

| Plant Type | Optimal Day Temp Range | Notes & What Happens Outside the Range |

|---|---|---|

| Cool-Season Vegetables (Lettuce, Spinach, Kale, Peas, Carrots) |

60°F - 70°F (15°C - 21°C) | The champions of spring and fall. Above 75°F (24°C), lettuce bolts (sends up a bitter flower stalk), spinach turns bitter, and peas stop producing. They can handle light frosts. |

| Warm-Season Vegetables (Tomatoes, Peppers, Cucumbers, Beans) |

70°F - 85°F (21°C - 29°C) | These are your summer stars. Growth stalls below 60°F (15°C). Extreme heat above 90°F (32°C) can cause blossom drop, sunscald on fruits, and poor pollination. |

| Tropical Houseplants (Monstera, Pothos, Philodendron, Snake Plant) |

65°F - 85°F (18°C - 29°C) | They thrive in stable, room-like temperatures. The biggest indoor killer? Cold drafts from windows or AC vents in winter. Below 50°F (10°C) can cause severe damage. |

| Succulents & Cacti (Aloe, Echeveria, Cacti) |

70°F - 85°F (21°C - 29°C) in active growth | They love warmth and can handle high heat with good airflow. The critical factor for them is a cool (40-55°F / 4-13°C), dry winter rest period to trigger flowering. |

| Herbs (Mediterranean) (Rosemary, Lavender, Thyme, Oregano) |

70°F - 85°F (21°C - 29°C) | They love heat and sun. Their flavor oils are often most concentrated when grown in warm, somewhat dry conditions. High humidity and cold, wet soil are their enemies. |

See? One size fits none. That basil on your windowsill and the succulent next to it want different things. And that's before we even get into root zone temperature, which is a whole other layer for plants in containers.

Becoming a Temperature Detective: How to Measure and Manage

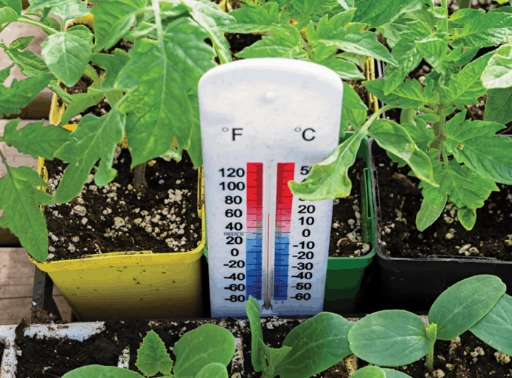

Okay, so you know it's important. But how do you actually work with it? You don't need a lab, just a bit of awareness and a couple of cheap tools.

Tools of the Trade

First, get a good digital thermometer with a probe. The kind you can stick into soil is gold. A simple indoor/outdoor hygrometer that shows min/max temperatures is also fantastic for tracking patterns. For outdoors, knowing your USDA Plant Hardiness Zone is the foundational first step—it tells you your average extreme winter low, which dictates what perennial plants can survive your winters. You can find yours on the official USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map.

Fixing Common Temperature Problems

Problem: "My indoor plants are sad in winter."

Likely culprit: Cold drafts AND dry air from heating. The spot by a leaky window can be 10-15 degrees colder than the rest of the room. Move plants away from drafty windows and heating vents. Grouping plants together can raise local humidity a bit. A humidifier is the nuclear option, but it works.

Problem: "My seedlings are tall, skinny, and falling over (leggy)."

Classic sign of not enough light, but often paired with too-warm air temperatures. The seedling stretches desperately for light, and warmth accelerates weak, spindly growth. The fix is more light (a grow light close to the leaves) and slightly cooler temps, especially at night.

Problem: "My tomatoes have lots of flowers but no fruit."

Hello, blossom drop! As mentioned, this is a classic temperature for plant growth issue. If it's early season and nights are cool, wait for warmer weather. If it's a heatwave, provide afternoon shade if possible (a sheer cloth works), ensure consistent watering, and wait for the heat to break. Some varieties are more heat-tolerant than others.

Pro Tip for Containers: Black pots bake in the sun and can cook roots. On a hot day, the soil temperature inside a black pot can be 20+ degrees hotter than the air temperature. Use light-colored pots, double-pot (place a black pot inside a larger decorative cachepot), or shade the container itself.

Advanced Play: DIF, Vernalization, and Heat Units

If you really want to nerd out, there are some fascinating concepts that commercial growers use.

DIF: This refers to the difference (DIF) between Day and Night temperatures. A positive DIF (day warmer than night) promotes stem elongation. A negative DIF (night warmer than day, or just a smaller difference) produces more compact, sturdier plants. Commercial growers use this to control height without chemicals.

Vernalization: Many bulbs (tulips, daffodils), fruit trees, and biennials (like carrots in their second year) require a prolonged period of cold (typically 32-50°F / 0-10°C) to initiate flowering. This is why you have to chill tulip bulbs before forcing them indoors. Without the cold, they won't get the memo to bloom.

Growing Degree Days (GDDs): This is a way to track heat accumulation. Plants develop based on heat, not just calendar days. Corn, for example, needs a certain number of "heat units" to go from planting to harvest. You can find GDD calculators online for specific crops. It explains why a cool, cloudy spring can set your harvest back weeks.

Let's Answer Your Burning Questions

I get a lot of the same questions about this topic. Here are the straight answers.

Putting It All Together: A Seasonal Checklist

Instead of just theory, here's what this looks like in practice through the year.

- Spring: Don't be fooled by a warm air day. Check soil temperature before sowing warm-season seeds or transplanting tomatoes. Use cloches or row covers to warm the soil and protect from late frosts. Start seeds indoors where you can control the temperature for plant growth.

- Summer: Monitor for heat stress—wilting in the afternoon, sunscald on fruits. Provide afternoon shade for sensitive plants. Mulch heavily to keep soil roots cooler and conserve moisture. Water deeply in the morning.

- Fall: Use row covers to extend the season for cool-weather crops as air temps drop. Get those garlic cloves and spring bulbs in the ground so they get their required vernalization period over winter.

- Winter (Indoors): Move plants away from cold windowsills. Reduce watering since growth has slowed in lower light and cooler indoor temps. Consider a heat mat for any tropical plants or seedlings you're starting.

Look, I'll be honest. When I first started gardening, I ignored temperature completely. I just planted when the garden center said it was time. Some things worked, many didn't. It felt random. Once I started paying attention to this invisible factor—checking soil temps, watching the forecast for cold snaps and heatwaves, choosing plants suited to my zone—everything became more predictable. More successful.

It's not about creating a perfect, controlled bubble. That's impossible outdoors. It's about understanding the rules of the game so you can work with them. You can choose the right players (plants) for your local climate, time your moves (planting) better, and give your team a helping hand (with shade cloth or frost protection) when the weather throws a curveball.

So next time you're puzzling over a plant problem, before you reach for the spray bottle or the fertilizer, just pause. Feel the air. Think about the soil. Check the thermometer. Ask yourself: "Is the temperature for plant growth right for this particular plant, right now?" More often than you'd think, the answer holds the key.

Reader Comments