You know the classic red-and-black beetle, the lucky charm of the garden. But that's just one chapter in its story. The full ladybug life cycle is a wild, four-act drama of transformation and appetite, playing out on the leaves of your plants. If you're trying to manage pests organically, understanding this cycle isn't just interesting—it's your strategic blueprint. I've watched this unfold for years in my own garden, and I can tell you, most people miss the most important part entirely.

What's Inside: Your Quick Guide

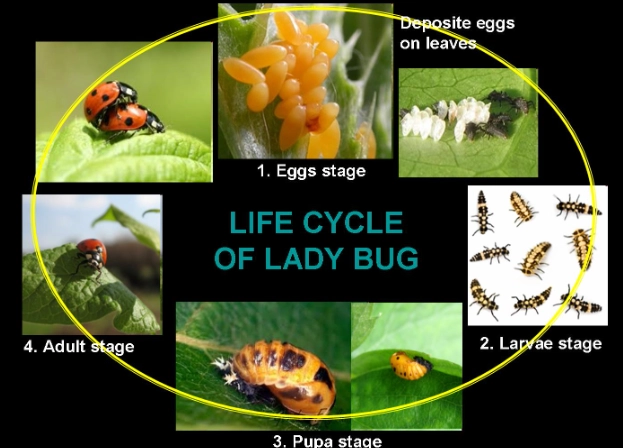

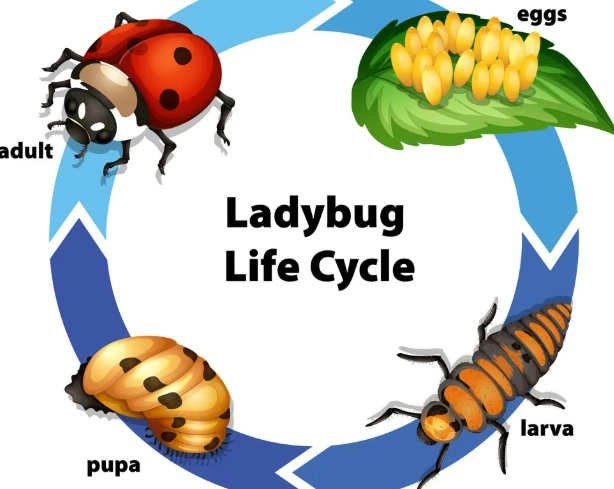

Stage 1: The Egg – A Strategic Launch

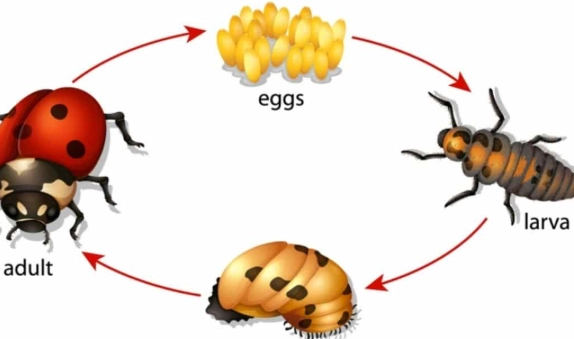

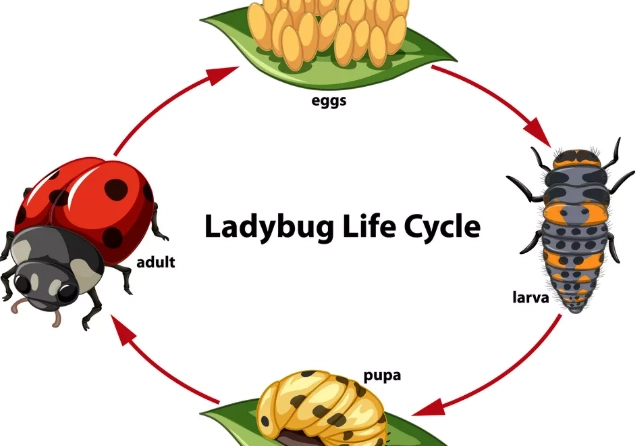

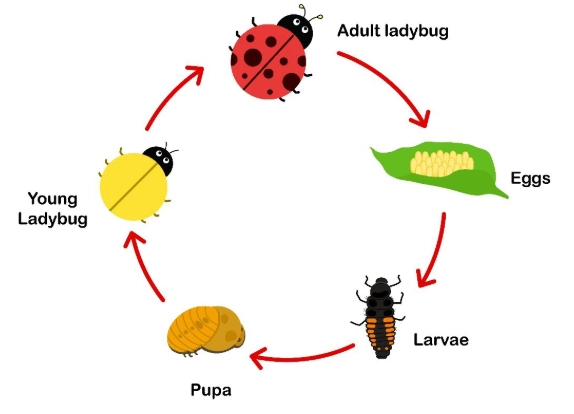

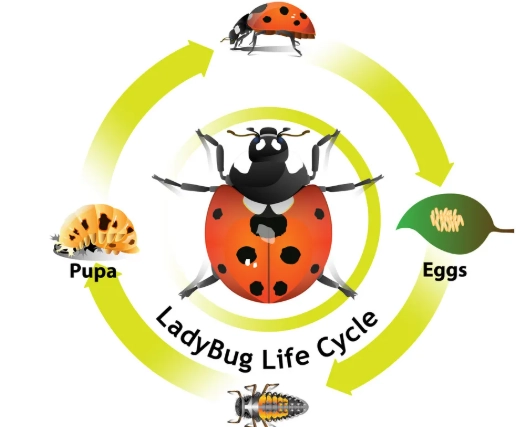

It all starts with a choice. A mated female ladybug doesn't just lay her eggs anywhere. She's a tactical predator. She scouts for a location with one key resource: food. Specifically, a colony of soft-bodied pests like aphids, scale, or mites.

She'll deposit a small cluster of 10-50 tiny, football-shaped eggs, usually on the underside of a leaf, right near the buffet. The eggs are bright yellow or orange—a color that might scream "eat me!" to us, but in the insect world, it's often a warning sign. They hatch in about 3-7 days, depending on temperature.

Stage 2: The Larva – The Unsung Aphid Assassin

This is the stage that changes everything for gardeners, and it's where almost everyone gets it wrong.

The larva that hatches looks nothing like a ladybug. It's an alien-looking, alligator-shaped creature, often black with bright orange or yellow markings, and covered in spiky protrusions. It's fast, hungry, and incredibly ugly (by cute beetle standards).

And it's an eating machine. This is the most voracious stage of the entire ladybug life cycle. A single larva can consume up to 400 aphids during its 2-3 week larval period. It goes through several molts (called instars), growing larger and hungrier each time.

Here's the critical mistake: gardeners see these weird, spiky bugs crawling on their roses and think "PEST!" and reach for the spray. You just wiped out your best organic defense. Learning to recognize the ladybug larva is the single most useful skill for natural pest control.

Stage 3: The Pupa – The Metamorphosis Chamber

When the larva is fully grown, it stops eating and attaches itself to a leaf or stem, usually in a sheltered spot. It curls up and its skin splits to reveal the pupa.

The pupa looks like a shriveled, orange-and-black blob, often with the last larval skin bunched up at one end. It's not mobile, and it doesn't eat. Inside, a biological miracle is happening: the tissues of the crawling larva are being completely reorganized into the flying adult beetle. This stage lasts about 5-10 days.

It's a vulnerable time. The pupa is defenseless. If you're spraying broad-spectrum insecticides, even organic ones like insecticidal soap, you can kill them at this stage too. Tread carefully.

Stage 4: The Adult – The Dispersal & Overwintering Phase

The adult ladybug emerges from the pupa soft and pale yellow. Within hours, its exoskeleton hardens and its iconic colors develop. This is the familiar beetle we all love.

The new adult's first job is to feed and fatten up. Then, its role shifts. While it still eats pests, a significant part of the adult phase is about dispersal and survival. Adults will fly to find new food sources and, crucially, to find sheltered places to overwinter (diapause) when temperatures drop.

They gather in large clusters under bark, in leaf litter, rock piles, or the cracks of buildings. The same adults that survive the winter will become active in spring, mate, and start the life cycle anew, laying the eggs that will produce the hungry larvae for your garden.

Your Garden Strategy: Work With the Cycle

Knowing the stages is one thing. Leveraging them is another. Your goal isn't just to have adult ladybugs visit; it's to have them live and reproduce in your garden. That means supporting every stage.

How to Attract and Keep Ladybugs

Think beyond the adult. You need to provide for the larvae and the overwintering adults too.

- Food for Larvae: Tolerate small aphid outbreaks. Yes, really. A few aphid colonies on your nasturtiums or milkweed are baby food for ladybug larvae. No food, no larvae.

- Food for Adults: Plant pollen and nectar sources. Adults supplement their pest diet with pollen. Good choices include dill, cilantro, fennel, yarrow, marigolds, and cosmos. Let some of your herbs flower.

- Water: A shallow dish with pebbles and water provides a drinking spot.

- Overwintering Sites: Be a little messy in the fall. Leave some leaf litter, a few logs, or a rock pile in a corner. This gives adults a place to hunker down for the winter.

- Chemical-Free Zone: Avoid broad-spectrum pesticides. They kill the larvae, pupae, and adults just as dead as the pests.

It's a shift in mindset. You're not just adding a bug; you're fostering an ecosystem that supports a full, reproducing population.

Common Questions (and Mistakes) Answered

Over the years, I've heard the same questions from fellow gardeners. Here are the real-world answers that go beyond the textbook.

The ladybug life cycle is a perfect, self-replicating pest control system. Stop thinking of them as just red beetles that show up sometimes. See them as eggs clinging to a leaf, as ravenous spiky larvae cleaning your plants, as pupae transforming in secret, and as adults seeking shelter in your garden's nooks. When you support that whole journey, you're not just gardening—you're building a resilient, natural defense that works for you, season after season.

Reader Comments